What Can We Do About JFK's Murder?

By Jefferson Morley

Nov 21 2012

It's time to demand accountability from the officials who failed to protect the president -- and then spent decades covering up their mistakes.

As November 22 comes around again, the memory of John F. Kennedy's assassination seems to be fading in America's collective consciousness, save among aging Baby Boomers like myself. Few people younger than me (I'm 54) have any memory of the day it actually happened. 9/11 has replaced 11/22 as the date stamp of catastrophic angst.

Yet that doesn't mean people have stopped looking for answers. The buzz surrounding the release of Jackie Kennedy's private conversations and Tom Hanks' upcoming Dallas movie shows that the public is still seeking new theories and clues. Two years ago on this site, I tried to answer the question "What Do We Really Know About JFK?" With the 50th anniversary of JFK's assassination approaching next year, the time for conspiracy theories has passed and the time for accountability is coming. Now is the time to ask, "What can we do about JFK's assassination?"

For one thing, we can use the Internet. The World Wide Web has birthed many conspiracy theories (most of them easily debunked), but it has also made the historical record of JFK's murder available to millions of people outside of Washington and the federal government for the first time. I have to believe this diffusion of historical knowledge will slowly clarify the JFK story for everybody.

For now, though, many American cultural elites continue to ignore the widely available facts. Earlier this year, in an exchange with sports columnist Bill Simmons, Malcolm Gladwell endorsed baseball statistician Bill James' theory that the fatal shot was fired by one of Kennedy's own Secret Service men. "When you have lots of trigger-happy people and lots of guns and lots of excitement all situated in the same place at the same time," Gladwell wrote, unburdened by evidence, "sometimes stupid and tragic accidents happen."

We can likewise treat with skepticism the CIA's latest interpretation of Kennedy's murder, proposed by Brian Latell, a former Cuba specialist at the Agency. In a new book, Latell has updated and modified the unconvincing "Fidel Castro did it" theory that was that was first put forward by the CIA within hours of JFK's death and is still believed by some.

Latell now argues that Castro knew (via his DGI intelligence service) that Oswald posed a threat to JFK, but he did nothing. The heartless Cuban communist, he says, played a "passive but knowing" role in JFK's murder. As I reported in Salon last spring, the most basic corroboration for these claims is lacking, as even an otherwise approving reviewer had to acknowledge in the CIA's Studies in Intelligence publication.

Latell is on firmer ground when he suggests that the media's obsession with "conspiracy" obscures other more nuanced explanations of JFK's death. But his allegations advertently highlight a truth that the CIA and my friends in the Washington press corps prefer not to acknowledge: There is a lot more evidence of CIA negligence in JFK's assassination than Cuban complicity.

The record available online confirms that Oswald was well known to the CIA shortly before JFK was killed -- so well known, in fact, that a group of senior officials collaborated on a security review of him in October 1963. And these officials assured colleagues and the FBI that Oswald, far from being a dangerous Castroite, was actually "maturing" and thus becoming less of a threat.

Read this CIA cable (not declassified until 1993) from beginning to end. You will see that Oswald's travels, politics, intentions, and state of mind were known to six senior CIA officers as of October 10, 1963. At that date, JFK and Jackie were just beginning to think about their upcoming political trip to Dallas.

Because the CIA is so often caricatured in JFK discussions, some background is helpful in understanding who wrote this document and why.

In the fall of 1963, Oswald, a 23-year old ex-Marine, traveled from his hometown of New Orleans to Mexico City. There he contacted the Cuban and Soviet Embassies, seeking a visa to travel to both countries. A CIA wiretap picked up his telephone calls, which indicated he had been referred to a Soviet consular officer suspected of being a KGB assassination specialist. Win Scott, the respected chief of the CIA station in Mexico, was concerned. He sent a query to headquarters: Who is this guy Oswald?

Scott's question was referred to the agency's counterintelligence (CI) staff. The CI staff was responsible for detecting threats to the secrecy of agency operations. Its senior members had been closely monitoring Oswald ever since he had defected to the Soviet Union in October 1959. Oswald had lived there two years, married a Russian woman, and then returned to the United States in June 1962.

Jane Roman a senior member of the CI staff retrieved the agency's fat file on Oswald. It included some three dozen documents, including family correspondence, State Department cables, and a recent FBI report stating said Oswald was an active pro-Castro leftist who had recently been arrested for fighting with anti-Castro exiles in New Orleans.

Roman and the CI staff drafted a response to the Mexico City station, which said, in effect, Don't worry. Ignoring the FBI report, the cable stated the "latest HQS info" on Oswald was a 16-month old message from a diplomat in Moscow concluding that Oswald's marriage and two year residence in the Soviet Union had a "maturing effect" on him. This inaccurate and optimistic message was reviewed and endorsed by five senior CIA officers, identified on the last page of the cable.

The CIA would kept the names of these highly-regarded officers -- Tom Karamessines, Bill Hood, John Whitten ("John Scelso"), Jane Roman, and Betty Egeter -- secret for thirty years. Why? Because the officers most knowledgeable about Oswald reported to two of the most powerful men in the CIA: Deputy Director Richard Helms and Counterintelligence Chief James Angleton.

These high-level aides could have -- and should have -- flagged Oswald for special attention. All five were anti-communists, well-versed in running covert operations and experienced in detecting threats to U.S. national security.

Karamessines, a trusted deputy to Helms, was a former beat cop who had served as a prosecutor in New York City before joining the CIA and becoming Athens station chief. Bill Hood was a former Berlin hand who oversaw all covert operations in the Western Hemisphere (and would later co-author Dick Helms' posthumous memoir). John Whitten, dogged and curmudgeonly, had built a reputation in the agency with his pioneering use of the polygraph.

Their complacent assessment of Oswald had real-world consequences.

In Mexico City, Win Scott never learned about Oswald's recent arrest or the fact that he gone public with his support for Castro. He stopped investigating Oswald. In Washington, a senior FBI official, Marvin Gheesling, responded to the CIA's benign assessment by taking Oswald off an "alert" list of people of special interest to the Bureau. When it came to the erratic and provocative Oswald, the CIA and the FBI were standing down.

Conspiracy or not, the CIA blew it. Oswald had been calling attention to himself. He had clashed with anti-Castro students in New Orleans, then contacted a suspected KGB operative to arrange an illegal trip to Cuba. By standard agency procedures of the day, he should have gotten closer attention. Instead, he got a pass from Helms and Angleton's staffers. Oswald returned from Mexico to Dallas where he rented a room in a boarding house under an assumed name.

Six weeks later JFK was shot dead, and the allegedly "maturing" Oswald was arrested.

After the assassination, Helms and Angleton stayed mum about their failure to identify Oswald as a threat. So did the agency hands who had vetted the accused assassin. The honorable exception was John Whitten, one of the few CIA operatives in the JFK assassination story who acted admirably. In 1963, Whitten served as chief of the Mexico Desk. He was a "good spy," specializing in counterespionage investigations to determine a suspect's ultimate allegiances. That was exactly the kind of information the U.S. government needed about Oswald after JFK was killed.

Whitten tried to mount an internal investigation of the accused assassin, drawing particularly on his contacts with pro-and anti-Castro Cubans in New Orleans and Miami. As Whitten later recounted in secret testimony to Congress, he was blocked by Angleton and then effectively fired by Helms.

His career over, Whitten retired and moved to Europe, telling his story only to those who had been cleared to hear it. He died in a Pennsylvania nursing home in 2001, his efforts to pursue the truth about Oswald concealed by his employer and forgotten by his country.

What did Helms and Angleton want to hide in 1963? Probably the same thing that the CIA and "Castro did it" conspiracy theorists hope to obscure today: U.S. intelligence failures contributed to JFK's wrongful death.

Neither Richard Helms or James Angleton was ever held accountable for their staff's faulty handling of intelligence about Oswald, and it is easy to see why. Both men were hard-line skeptics of JFK's liberal foreign policy who found President Lyndon Johnson a much more capable commander in chief. Both had friends and allies in high places. (Angleton was close to J. Edgar Hoover; Helms was lionized by syndicated columnist Stewart Alsop.) .Both used official secrecy to prevent the Warren Commission from asking too many questions. After the Warren Report came out, they kept their jobs and enjoyed the respect of the Washington press corps, at least for a while.

President Lyndon Johnson named Helms to be CIA director in 1966 and he served until 1973, gaining a well-deserved reputation as The Man Who Kept the Secrets. Helms played an inscrutable role in the Watergate scandal that brought down President Richard Nixon and later pled guilty to lying to Congress. The "gentlemanly planner of assassinations," as one journalist dubbed him, died in 2002. His widow, Cynthia Helms, has just published a memoir defending his good name.

Jim Angleton remained chief of the Counterintelligence Staff until 1974, when he was disgraced by the revelation he had overseen a massive illegal spying program on Americans. He died in 1988. His espionage exploits have inspired many book and several Hollywood movies (most recently The Good Shepherd, starring Matt Damon). Angleton's close monitoring of Lee Harvey Oswald from October 1959 to October 1963 was first documented in historian John Newman's groundbreaking book, Oswald and the CIA.

So those Americans still seeking to understand the meaning of November 22, 1963, in American history, would do well to consider the legal culpability of two titans in the annals of the CIA, Richard Helms and James Angleton. Their negligence could spawn any number of new conspiracy theories: Were they (or other national security mandarins) using Oswald in a sinister maneuver against JFK? Or did their staffs use Oswald in service of a legitimate secret operation, only to realize too late that he was a lone psychopath?

Ultimately, what matters most is that these decorated CIA men were criminally negligent -- or, at the very least, clueless about a clever assassin. If we honor the memory of JFK, they should be held responsible. Their complacent and inaccurate reporting on Oswald before JFK's assassination, and their evasion of responsibility afterwards, are central to the confusion that sadly still clouds the case of the murdered president.

That much we know. Some day, we may also have access to deeper information - for instance, the records of George Joannides, a decorated Miami-based undercover officer (now deceased) who knew about Oswald's Cuban contacts and who reported to Dick Helms in 1963. (In 2003 I filed a Freedom of Information Action Act lawsuit for his files in 1963. Nine years later, my case is still pending.)

We can't do much about the JFK tragedy at this late date, but we can acknowledge that CIA negligence led directly to the president's death. The officers who obscured information about Oswald should be stripped of any medals or commendations they received for their job performance in 1963. Fifty years later, it's time for accountability.

Jefferson Morley - Jefferson Morley is a former editor at The Washington Post and the author of Our Man in Mexico: Winston Scott and the Hidden History of the CIA. He writes about JFK's assassination at JFKfacts.org.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

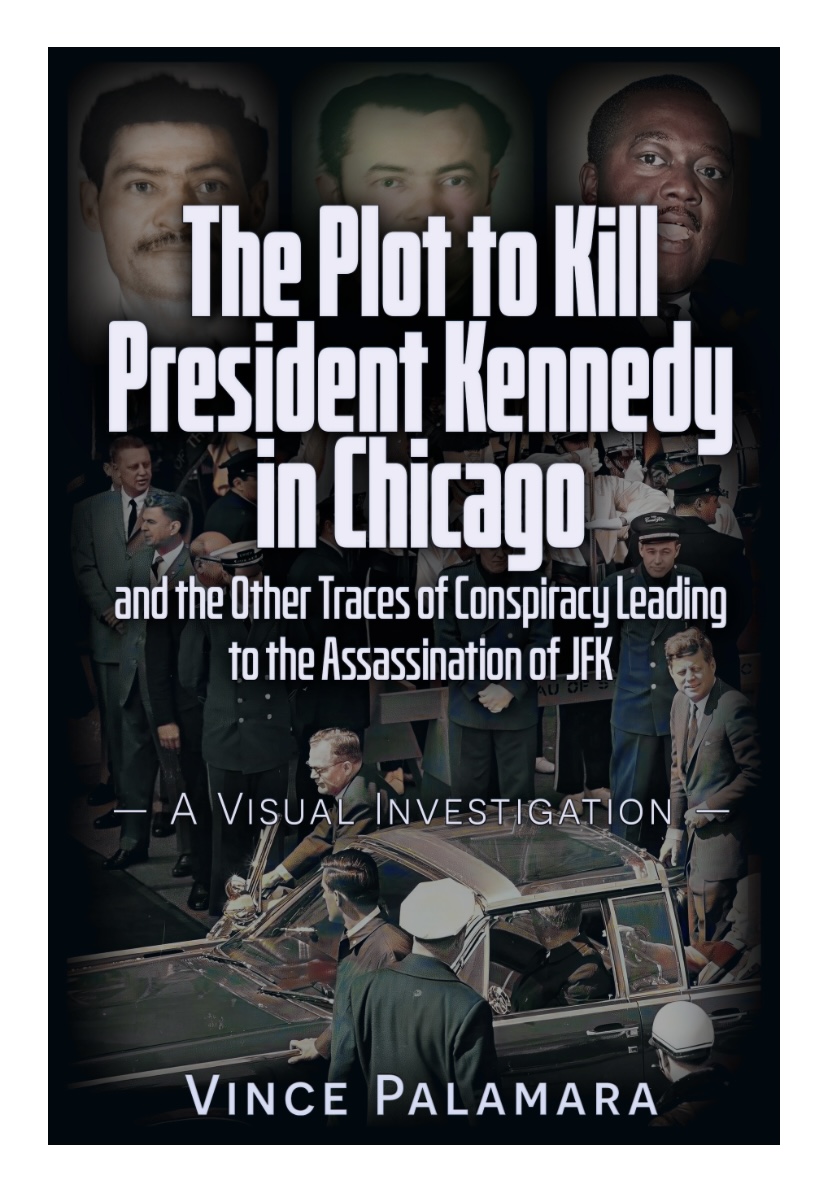

![VINCE PALAMARA [remember to scroll all the way down!]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjSZ-Z_puqnjl3UgdiJxBenMyIMaFhmBD-PYQUsxCtFS4UF7dJQB6n32rt9a0ZqFRPmuBoukhrMZxv6LOD9GoUGPiaShO3wj_8xL98obRAsUbIf0mXutzbq7jKDrCp8Y-Y0k9rnS5ARjQQ/s1600/11.jpg)

![CHAPTER 8 OF ARRB FINAL REPORT [I AM IN THIS REPORT, AS WELL]...HMMM---THE SECRET SERVICE DESTROYS](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEimGbOuG69gW-cgAbsfjd8p8PD-subznIjcsQXUSFq560o_kiXunf9TcH0fkOqmWuK73id6m5TyVMhWcfBrPUEee6JLbvqNZKdIVQa5Drcz568Ue6GZdf_PUtLuLwPDcucv3gOn5KGBZPw/s1600/DSCF0462.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment